Maybe I should be spending the time I devote to knitting on some kind of reskilling instead.

This year, which turned into a full-on knitting New Year, that sense of anxiety hit me again. Or rather, it’s been hitting me every year since I passed the midpoint to retirement. A one-year plan stretches into ten, then twenty, and eventually morphs into anxiety about old age. It probably doesn’t help that the New Year’s money my daughter gets from my mother-in-law sometimes looks to me like a pension payment.

My first candidate for “learning again” was English conversation. If I started now, I’d have about twenty years to study before retirement. That’s long enough for a newborn baby to grow up and run the Hakone Ekiden. Surely I’d become reasonably fluent by then. It could widen my options for a second career or a senior-side job.

But while I feel anxious, I don’t actually hurry. In fact, I can’t even muster the motivation.

I work for a thoroughly inward-looking Japanese company, practically in a state of national isolation. I can’t bring myself to spend what little allowance I have on English lessons that won’t lead to a raise. And on top of that, I’ve learned how to knit. The time I spend slouching on the sofa, knitting lazily, is as sweet as opium. Time melts away instantly; there’s never enough of it, and I have no intention of restraining myself. In other words, I’m an addict. Not to opium—knitting. Just to be clear. There was no way I could study English without spending money or sacrificing my knitting time.

Or so I thought.

Maybe there was a way after all. What if I knitted while talking in English with AI?

Signing up for classes, whether in person or online, felt about as realistic as science fiction. But starting small on a smartphone—maybe that I could manage. No risk, after all.

Suddenly, I felt motivated. I sank into the sofa. My usual relaxed posture, but with my back just a little straighter. In my hands was a red neck warmer I was knitting for my daughter. My smartphone lay beside me. I launched ChatGPT in voice mode.

“Chat GPT, can you hear me?”

“I can hear you loud and clear! Let me know if there’s anything I can help you with.”

A handsome voice. Fresh and breezy, like a radio DJ. And on top of that, he’s the most knowledgeable being in the world. Since I had the chance, I decided to ask him about basic knitting knowledge. I’m a beginner, so we went with a simple Q&A format.

“What do you say omote-ami in English?”

(What do you call a knit stitch in English?)

For now, vibe over grammar. I tried to sound like a native and pronounce it properly. My tongue and lips weren’t used to English movements at all. But that was fine. He didn’t laugh or sound annoyed.

“In English, omote-ami is usually referred to as the ‘knit stitch.’ It’s the basic stitch used in knitting, and it’s one of the fundamental techniques in the craft.”

Knit means “to knit,” and stitch means “a seam.” Put together, it’s like “a knitted seam.” Are you knitting or sewing? Which is it? What a weird name! I love it.

“Wow! Thank you. So what do you say ura-ami in English?”

(Then what about the purl stitch?)

I can’t believe I actually said “wow.”

“In English, ura-ami is called the ‘purl stitch.’ It’s the counterpart to the knit stitch, and together they form the basis of many knitting patterns.”

“What’s purl?”

“The word ‘purl’ itself has the nuance of wrapping or twirling, which describes the characteristics of this knitting method. It’s a very simple and basic expression.”

So ura-ami is a purl stitch. A “wrapping stitch.” That makes sense—you do kind of twist it around.

Of course, at first I couldn’t understand a thing. Just a string of sounds. It felt like it started and ended in an instant. Why is English always so fast? But—again. Again. Again. Being able to ask without hesitation is one of the best things about AI. After repeating it enough times, my ears started to catch the words I already knew.

Knitting while listening also seemed well suited for listening practice. When I knit, my entire field of vision is filled with needles and yarn. Compared to a smartphone or computer, there’s far less visual information. In exchange, my ears seemed to open up. At least, that’s how it felt to me.

Still, why were knit stitch and purl stitch translated into Japanese as omote-ami and ura-ami? And when did knitting even arrive in Japan in the first place? “When did knitting originate?” “What’s the oldest known knitted object?” “Can you show me a university website?” As I knitted one stitch after another with soft wool, I bombarded the AI with questions about the history of knitting.

When the other party is AI, I don’t get that urge to “speak correctly.” I can comfortably play the role of a cool, fluent version of myself while confidently making mistakes. Nonsense is fine. First, it’s about enjoying the feeling of speaking with my mouth. Maybe this is how babies feel. And yet the AI still responds properly every time. It really is amazing.

An unexpected effect came from the movement of my hands manipulating the needles and yarn. Some people get extra animated with their gestures when they talk seriously. A rapper I know once said, “I can’t freestyle if I’m standing perfectly still.” The connection between hands and mouth. Knitting was exactly that. Knit knit purl purl, knit knit purl purl. Keeping my hands moving at a steady rhythm made my mouth feel lighter; the conversation didn’t stall. Maybe the movement of the hands acts like a springboard for words.

I used to think the charm of knitting was its quiet solitude. But chatting while knitting has a different kind of appeal. Being absorbed in my own world, yet feeling someone beside me at the same time. A walk-like conversation, where boundaries blur—maybe that’s something I’d long forgotten. Knitting circles exist in communities for a reason.

With AI, I could do that alone. Even me, with 46 years of being shy around people. AI + English conversation + knitting. A true new combination—an innovation.

Ding-dong.

The doorbell rang. My daughter stood on tiptoe to peek at the intercom screen. “Coming!” Her classmate, K, had come over to play. Judging by her surname, she was probably Chinese. “Welcome!” “Sorry to bother you—happy New Year.” Her pronunciation was crisp and clear. My daughter goes to a public elementary school, but there are kids of many nationalities and skin colors. They all speak Japanese fluently. I genuinely, deeply, wholeheartedly respect that.

The girls took over the sofa and started playing on the Switch. “I got Switch 2. It hasn’t arrived yet.” “Oh nice. I want it too…” Banished to the table, I caught my daughter glancing at me. I understand “I want it too,” damn it.

In fact, I’m the only one in the Kusaka family who’s hopeless at English. My wife is fluent enough to argue with airport security officers overseas, and my daughter has been attending English classes since she was little. I’ve heard that in some parts of China, kids start learning English in elementary school too, so maybe K was one of them.

Their common language was games. English, Japanese, and body language were just hints. Even so, it was amazing to see their coordination develop as they played together. Kids today, huh.

Maybe knitting used to be like this too.

According to AI, knitting spread from the Middle East to Europe. Naturally, there must have been language barriers along the way. Knitting techniques, especially, are hard to convey through words or writing alone. Hands-on teaching would have been inevitable.

If that’s the case, then knitting together across ethnic lines must have been an important form of communication. A kind of “knit-communication,” if you will—something more physical than language, closer to music or dance.

Perhaps knitting has survived to the present day because it absorbed so many different cultures. Maybe simply because it was more fun that way. Watching the girls shout F-words in perfect pronunciation at Bowser on the screen, I found myself thinking that.

Now, a confession. Partway through—no, long before the end—I had switched the AI back to Japanese. The history of knitting was just too fascinating.

One theory says that knitting with two needles emerged about a thousand years ago. Considering that Homo sapiens appeared 200,000 to 300,000 years ago, needle knitting is actually a “new technology” in human history. Incredible. And yet the origins of knitting itself stretch back too far to trace—probably to before recorded history. So what happened during all that time? There are, of course, many theories.

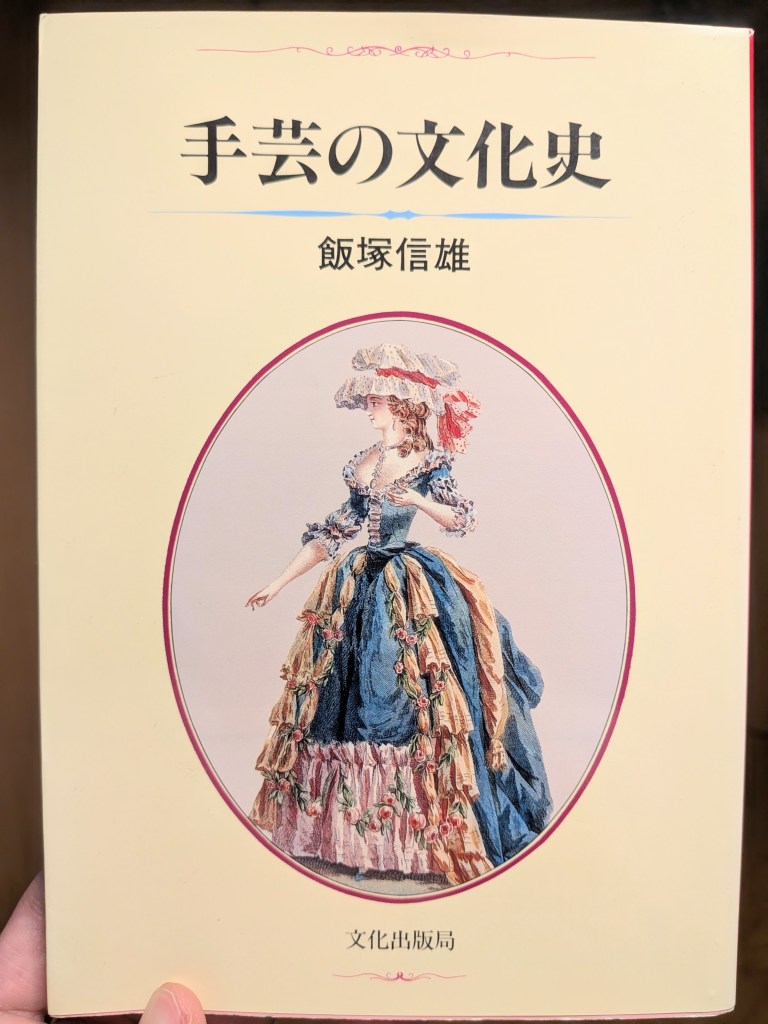

These days, I’m reading A Cultural History of Handicrafts by Nobuo Iizuka (Bunka Publishing Bureau, 1987). I’ll count that as reskilling too—for now.

Finished my daughter’s neck warmer. A revenge project from last year. I used 100% soft wool so it wouldn’t itch her third-grader skin—and she stretched it out anyway, without a second thought.

“Forty years have passed since its publication. In that time, accepted theories have been overturned. Knitting leaves little physical evidence—it’s ephemeral by nature. And the fields involved are vast: cultural anthropology, rchaeology, folklore, industrial history. The history of knitting is fascinating.

コメントを残す