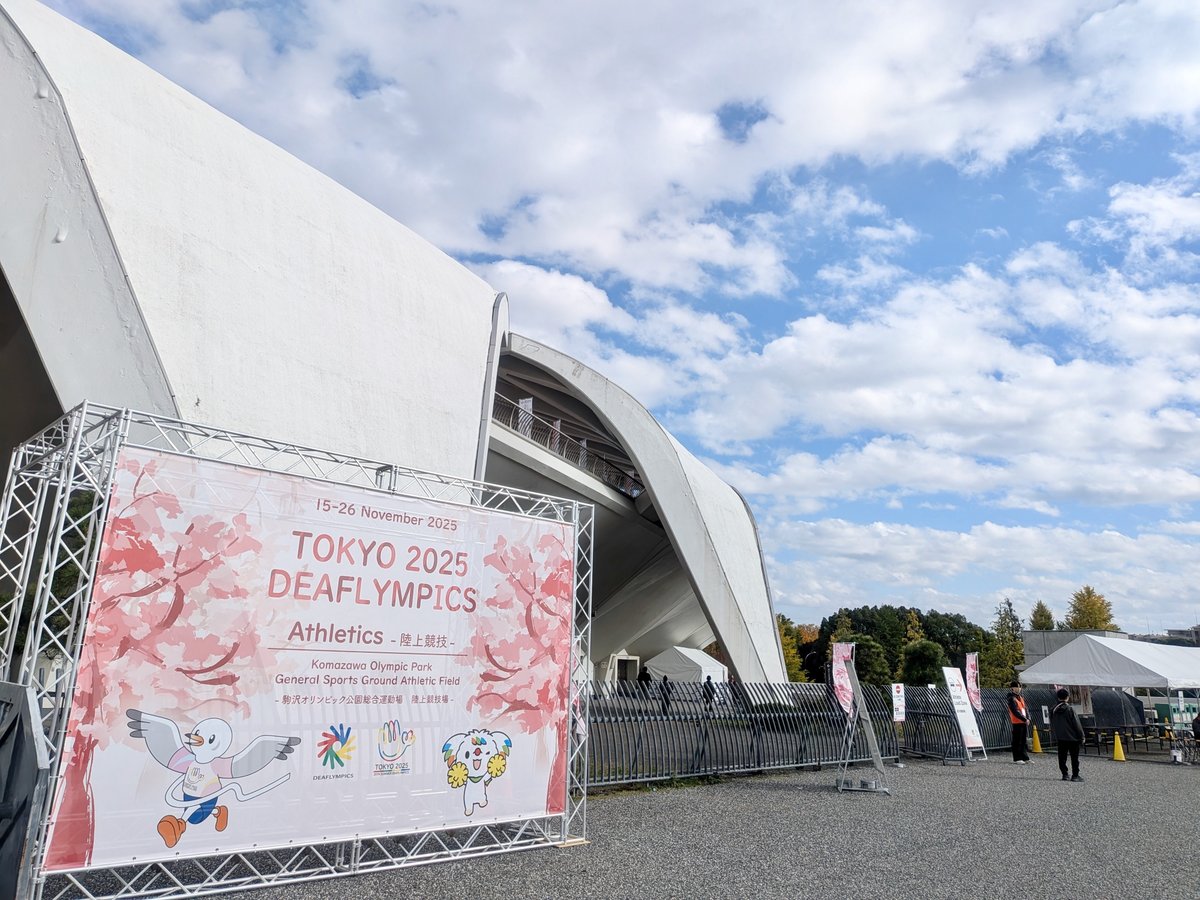

The Deaflympics are being held in Japan for the very first time—and it’s fascinating.

“Deaf” plus “Olympics,” literally an Olympic Games for people who are deaf or hard of hearing. The event is held once every four years, and this year marks the 25th edition—a milestone. Its official title is the Summer Deaflympics Tokyo 2025. More than 3,000 athletes from 81 countries and regions are taking part.

What I love most about the Deaflympics is its DIY spirit. The organizing team—including the Japanese Federation of the Deaf, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, and the Tokyo Sport Benefits Corporation—handles everything themselves, from securing sponsors to running the event, with the help of volunteers. Unlike the Olympics and Paralympics, nothing is outsourced wholesale to ad agencies or commercial contractors. Festivals are fun precisely because people make them themselves—and because it brings more people together.

Another thing: they make full use of what already exists. No massive spending on new stadiums or flashy facilities built with taxpayer money or corporate sponsorship. It all feels refreshingly healthy.

And no wonder—the movement began in 1924. This year marks the 100th anniversary. The Deaflympics have a depth of history and experience behind them. (For comparison: the FIFA World Cup began in 1930, and the Paralympics in 1948.)

To this DIY spirit and resourcefulness is added a philosophy of mutual understanding, peace, and solidarity. And as a festival, it has the kind of lively energy that I can’t help but associate with hip-hop culture. I love that.

Plus, all tickets are free. No reservations needed. I love that even more.

Watching Volleyball: The Players Were… Dancing?

But truth be told, volleyball was the only sport I managed to see live. On Day 3 of the Games, Sunday, November 16, I headed to Komazawa Park.

The first surprise: the sheer number of spectators.

I mentioned the crowd to one of the volunteers. “This is actually considered empty,” they said. “There was a Japan match this morning and it went over capacity. We had to restrict entry, and it was only a preliminary match!” That got me even more excited.

Finally, I reached the stands.

The matches underway were Turkey vs. Ukraine (men’s) and Turkey vs. Canada (women’s). Even someone like me, who barely knows volleyball, was struck by how full the venue was.

The games were genuinely thrilling, not only because of the intensity of play but because of so many things I learned for the first time.

The biggest surprise: the substitutes waiting by the court. The women’s teams.

Were they… dancing?

The red team, leading the match, moved their arms in big motions—almost like a monkey dance. At one point, they even linked arms and did a kind of line dance.

By contrast, the black-uniformed team, struggling in the match, stood perfectly still.

Depressed…

It puzzled me. I’d never seen athletes literally dancing on the bench.

This is just my guess: in team sports, players normally shout encouragement to boost morale. But at the Deaflympics, that’s not really an option. So they use gestures—body language. And since athletes are human, when their team is winning, the gestures get bigger; when they’re losing, they shrink.

Of course, cultural differences, team personality, and individual character also play a part.

On that note: I assumed the lively red team was Canada—“Ah, must be that Western vibe.” Turns out they were Turkey. People in Muslim-majority countries are that exuberant? My mistake. Without spoken language as a clue, even identifying nationality becomes tricky. It made me realize just how much I rely on assumptions and stereotypes.

Another surprise: Deaf athletes do clap and shout. Loudly. Very loudly.

I had imagined a quiet venue where only the sound of the ball and sneakers echoed. Totally wrong. They yell, roar, and cheer just like any intense sports crowd. The energy is contagious.

And of course—why wouldn’t they? How could anyone stay silent in such heated competition? Again, my own ignorance was laid bare.

After the match, the audience gave enthusiastic applause—even to the opposing team. Canadian supporters cheered warmly for the victorious Turkish players.

Fluttering both hands with palms open is applause in sign language. It seems to be universal. (Side note: the red uniforms were Turkey; the people in red shirts in the stands were Canadian supporters. Confusing!)

Deaflympics Square: A Hub of People and Technology

That’s where I spent much of my time, which explains why I only caught volleyball.

Deaflympics Square served as the operations center, transport hub, media center, and practice venue. It also hosted exhibitions about Deaf sports and Deaf culture, along with demos of universal communication (UC) technologies.

At the National Olympics Memorial Youth Center in Sangubashi, visitors were already signing at the station.

The central courtyard was lined with booths from companies and organizations. There were merchandise stands and food trucks too.

The merch booth here was also extremely popular—people buying goods as if stocking up for multiple visits.

Lots of foreign visitors as well. I overheard someone laughing, “Ugh! Japanese Sign Language and your country’s sign language are totally different! Hahaha!”

Conversations in sign language were happening everywhere. Japanese Sign Language, International Sign, Japanese—multiple cultures overlapping. It was quiet, yet not silent. Strange, lively, and wonderfully comfortable.

I was even approached by volunteers in sign language. Oh—I’m the minority here. It was a refreshing experience, and it made me realize how rich and established sign language is as a cultural-linguistic world.

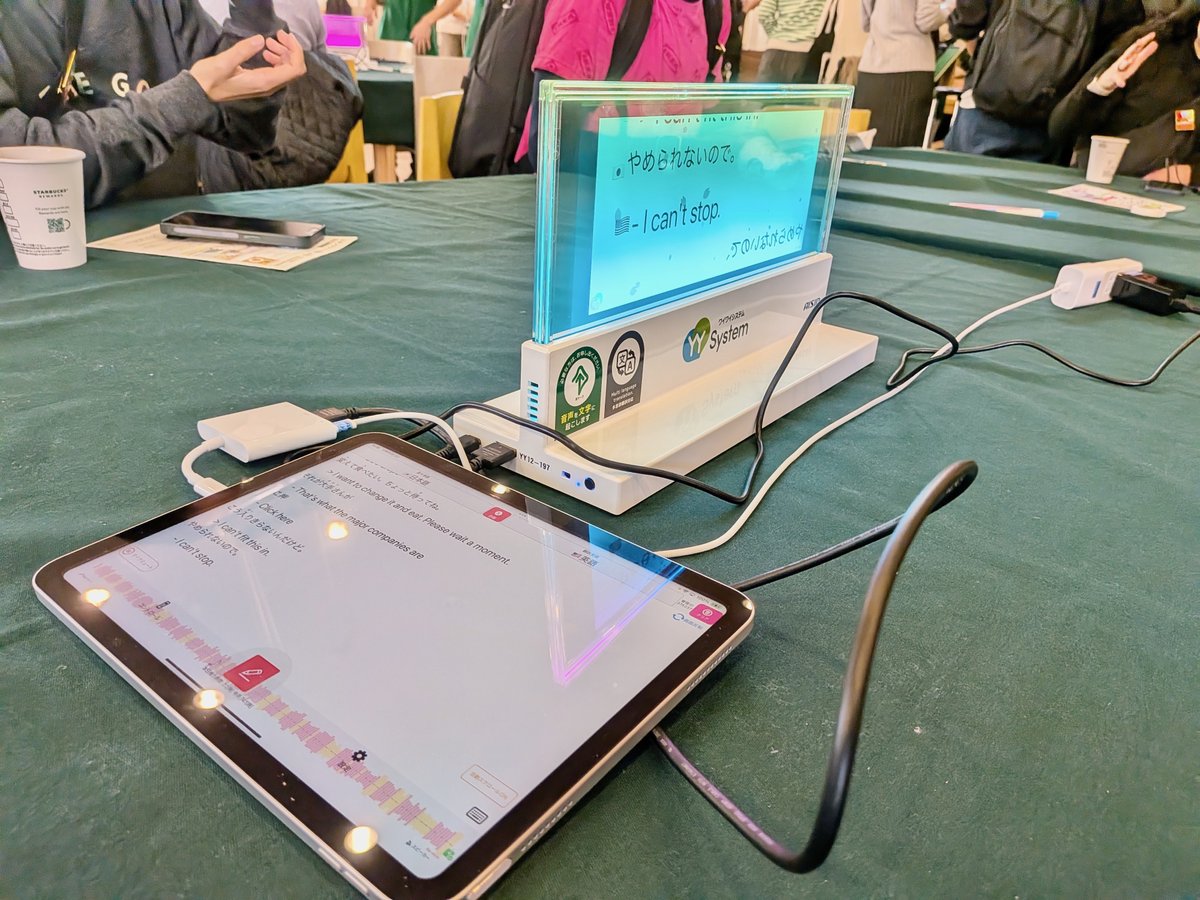

The Culture & Technology Pavilion.

Inside one of the buildings—something like a university or government facility—companies and organizations had set up their exhibits along the hallway. Visitors browsed eagerly.

It was simple, cost-conscious, and unpretentious.

Not the grand scale or flashiness of the Olympics or Paralympics—but that’s the beauty of it.

It felt like a slightly upscale cultural festival for grown-ups.

There was also a café area where athletes, staff, and visitors mingled. Despite the crowd, the shared language of sign created a unique atmosphere—vibrant yet calm. To me, it felt like a wonderfully curious space.

New products from ventures are also placed on the tables, and you can try them out.

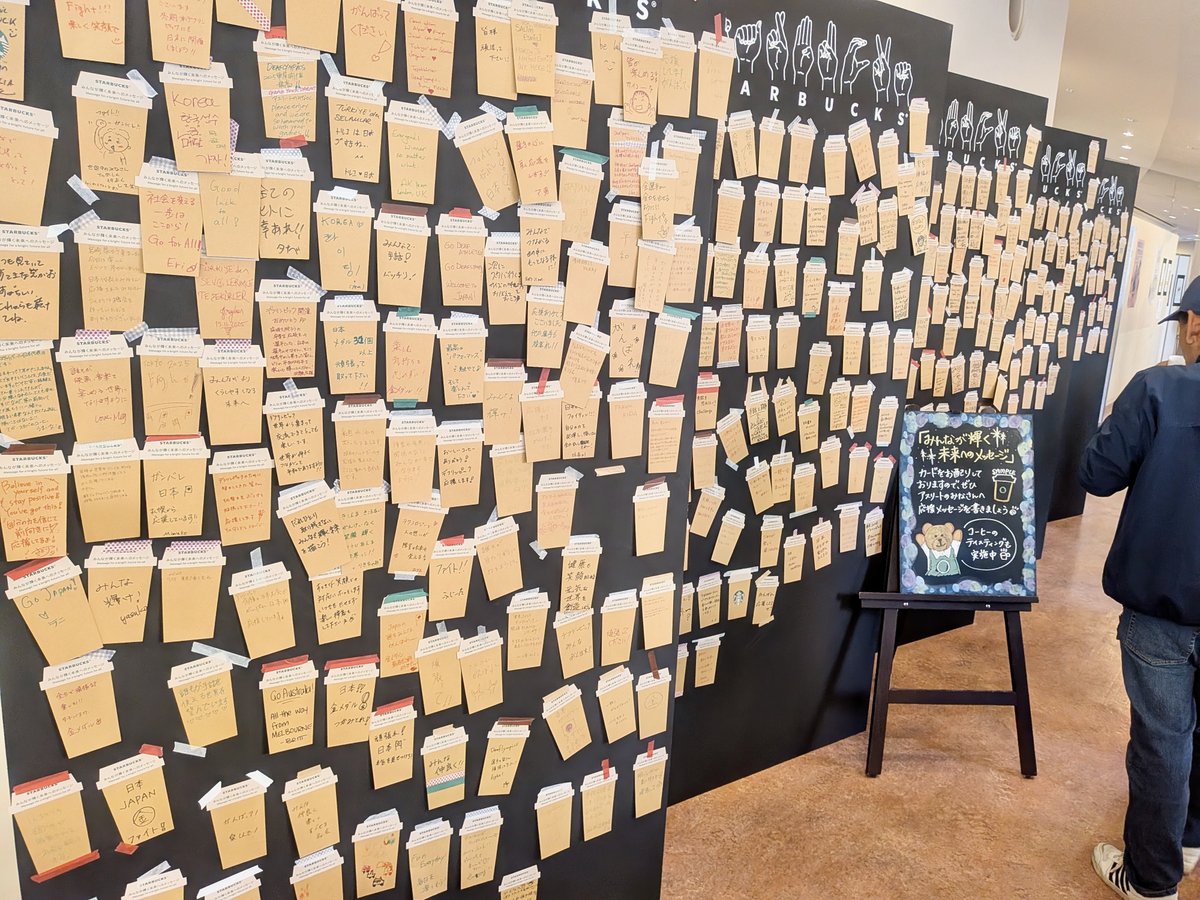

On the wall next to the café area, there was an entire section covered with message cards for the athletes. Each card was shaped like a paper coffee cup, filled with handwritten cheers and well-wishes. Some people even stopped there to take photos, treating it like a mini photo spot.

The livestreams are worth watching too. You can see events unique to the Deaflympics.

This year’s Deaflympics is being held across Tokyo, Shizuoka, and Fukushima. Not everyone in Japan can travel to the venues, of course. That’s why there are livestreams and archives—and those are fascinating in their own way.

Here’s a scene from the opening ceremony. The performance tells a story that begins in the era when sign language was banned in Japan, and moves toward a future of connection and unity. I didn’t win the ticket lottery, so I watched it from home—tragic. I really wish I could have seen it live.

By the way, when I was watching it live on November 15 (Sat), there were only about 5,600 concurrent viewers. I couldn’t help feeling a little sad about that. But as I’m writing this now, just four days after it was posted, the view count has already reached 110,000. So people are watching after all.

And here’s the track and field finals.

What makes it especially interesting is the commentary. The play-by-play and analysis are not only spoken but simultaneously subtitled, and there’s a Japanese Sign Language interpreter on screen as well. There’s also a version in International Sign with English subtitles.

But wait—you might think that if there are subtitles, a sign language interpreter isn’t necessary. I did a little research on this myself.

For many Deaf people, sign language is their first language. Subtitles can sometimes be hard to read or difficult to follow in real time. And subtitles can contain errors when generated simultaneously.

Sign language also conveys information through facial expressions and body language. Some people use Japanese Sign Language, others use Japanese-adapted sign or spoken-language support, and some rely on hearing aids to supplement audio.

For this reason, accessibility as a form of information provision fundamentally requires multiple channels—it’s essential.

This is what I found, though I’m not an expert, so I’m not certain if it’s the full picture. Someday, I’d like to ask someone on-site to confirm.

Certainly, it’s better to have multiple channels and options—and that’s how it should be. This applies to other social issues as well: having more choices shouldn’t hinder or block anyone else. Experiencing and understanding this firsthand is incredibly important when thinking about and shaping future social systems, and it highlights the significant role events like this can play.

This is basketball. There were no real-time subtitles or sign language interpreters. Perhaps there aren’t enough resources to provide them for every game—something to work on in the future.

By the way, Japan’s men’s team narrowly defeated Argentina 81–79, claiming their first victory of the tournament. A two-point difference! Just one basket! Ranked 19th in the world, Japan pulled off a huge upset against fifth-ranked Argentina.

Since Deaf athletes cannot—or may not—hear the referee’s whistle or buzzer, visual cues are provided instead. LED lights are installed on the goalposts and in front of the table officials’ seats, lighting up in sync with the sounds to ensure players receive the necessary visual information.

Another point of interest: there are sports that exist in the Deaflympics but not in the Olympics or Paralympics—namely, bowling and orienteering.

Indoor sports and outdoor sports. Facility-based sports and nature-based sports. Some involve just a few steps; others require running non-stop. It’s fascinating that such opposite types of activities can both be unique to the Deaflympics.

The livestream of orienteering, in particular, is full of clever solutions. The event takes place in Hibiya Park in Tokyo, with athletes running all over the area. There’s no way for cameras to follow them closely. So how do they broadcast it? It’s impressive how they overcome a challenge that even the Olympics or Paralympics might shy away from. The Deaflympics really show grit.

It was my first time seeing orienteering as a sport—actually, my first time realizing it was a sport. I can’t help but wonder what kind of path leads someone to discover and compete in orienteering… The world is vast.

The games will continue until the closing ceremony on November 26 (I didn’t get a ticket for that one either!). I plan to watch as much as I can.

I’m sure it will be a chance to encounter new cultures, surprises, and moving experiences. Whether you’re interested or not, it’s worth checking out!

And who knows when you’ll be able to see the Deaflympics in Japan again… maybe 100 years from now!

コメントを残す