From Pokémon to Art Brut Exhibition

This is no good. At this rate, Golden Week will turn into Violet Week. To be precise, it will turn into Pokemon Violet Week. What’s more, it’s already halfway over.

My daughter stares obsessively at the screen, pressing a button to send Pikachu into battle. Again and again. Wait. Don’t use biodiversity as your proxy war. Stop overfishing. It’s unnecessary killing.

So I invited my daughter out. “Dad, there’s a place I want to go. Do you want to come with me?” “No.” The 6-year-old didn’t even glance in my direction. “Let’s go to Baskin-Robbins, the arcade, and Village Vanguard.” “Oh well. Where are we going?” Just like Monster Ball, I got my first-grader daughter.

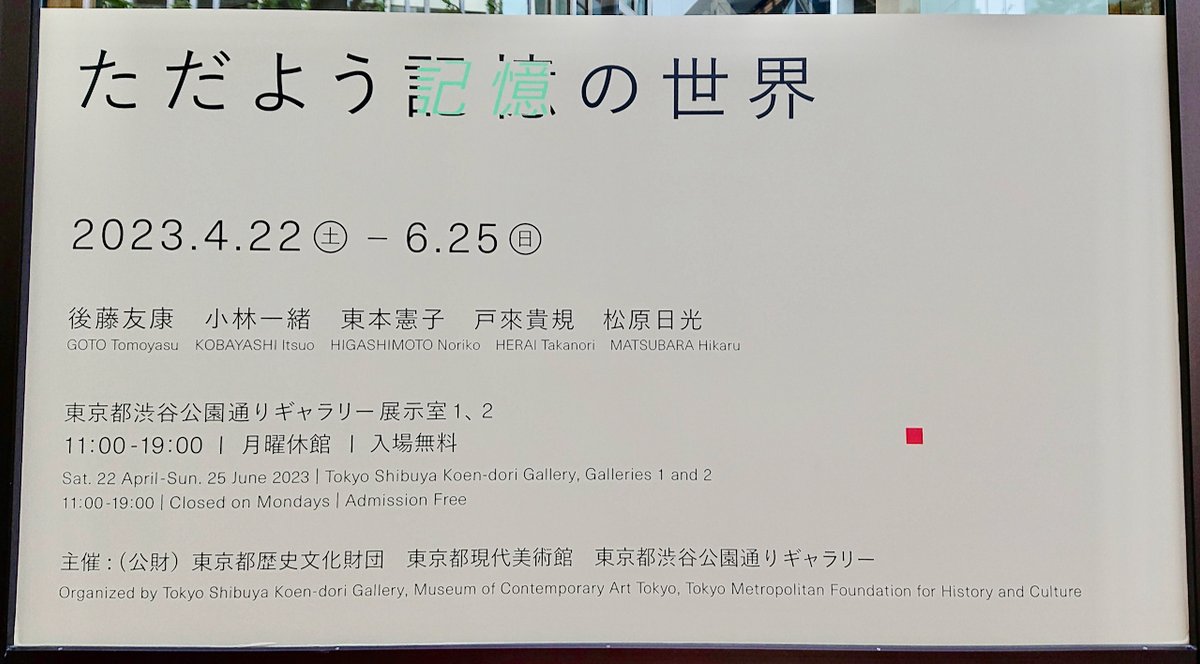

We took him to the Shibuya Koen-dori Gallery in Tokyo . The exhibition was called ” Art Brut Then & Now Vol. 3: A World of Floating Memories.” It featured works by artists active in the art brut scene both in Japan and overseas, especially those with some kind of disability.

The gallery was on the first floor of the Shibuya Ward Labor Welfare Hall. The name sounds corny. The worn-out floors give an idea of how old the building is. The corridors are narrow. According to the Shibuya Ward website, “This is a facility where workers can easily participate in sports and club activities.” It’s sober. When it was built, they probably didn’t expect children to visit.

My daughter suddenly made a dash for the deeper part of the building. The sound of a child’s footsteps echoed out of place. She ran towards the work at the entrance to the exhibition. There, “What’s that?” was displayed on the wall.

I can hear the colors. I’m swept away by the colors.

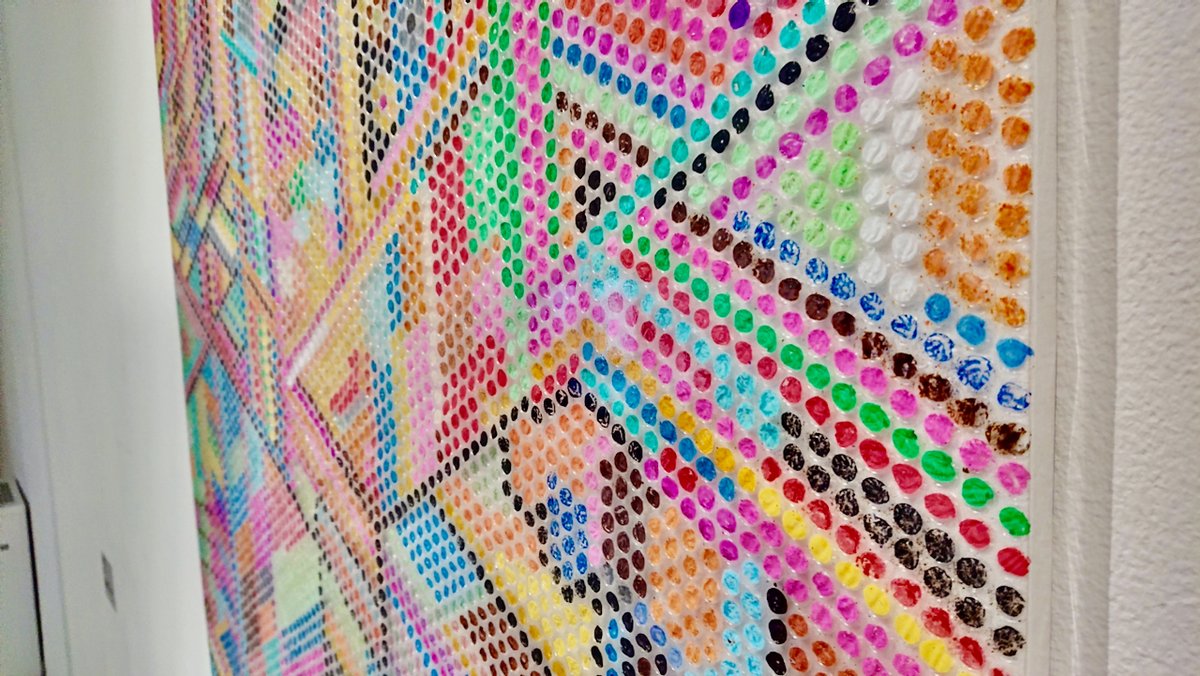

There are two large cushion-sized pieces. From a distance, both of them have a rough texture. It’s as if they were made by drawing noise. And they are very colorful. I wonder how many colors they used. The old Famicom screens often had glitches like that. In front of the pieces, my daughter’s back is also frozen.

However, as I got closer, step by step, my impression changed; far from being frozen, I began to sense a sense of dynamism. And so I discovered the true nature of the work. “Bubble wrap?” Yes. Bubble wrap. The kind of bubble wrap used for cushioning fragile items. “What? Seriously?”

The work was made up of hundreds of bubble wrap pieces that had been painted over one by one, forming a pointillism painting.

“Don’t touch me!” My daughter flinched and pulled her finger away. I couldn’t help but raise my voice. But I understand how she feels. I totally understand. It’s just popping. Poke, squish. And preferably pop. In fact, that’s the correct way to use it. The 6-year-old and 43-year-old looked at each other with their hands clasped behind their backs like prisoners, cross-eyed. If I were the work of art, I’d want to say, “You’ve got a bad mouth,” and add, “Especially the 43-year-old,” at such close range.

“What do you see?” “There’s a K here, and here too.” “That’s a Y.” “There are a lot of triangles.” Even my daughter and I see different things. There is no specific motif in the picture, nor is it a geometric pattern. As she fills in each little bit, lines are created, surfaces are born, and shapes are formed. These lead to the development of the adjacent lines and surfaces, and before you know it, it has become a tapestry. Perhaps. There is no pattern. But it is not completely random either. She draws things that only she can see. The overwhelming originality is conveyed in an instant. Above all, it is undoubtedly beautiful. If you do it with a click. You will surely hear the sound of colors popping. It

was not only beautiful, but also pleasant to look at. It was a strange feeling. “I could look at this forever,” my daughter whispered to me as I was fascinated. “Dad, over there,”

my daughter’s index finger finally got a turn. I looked at what it was.

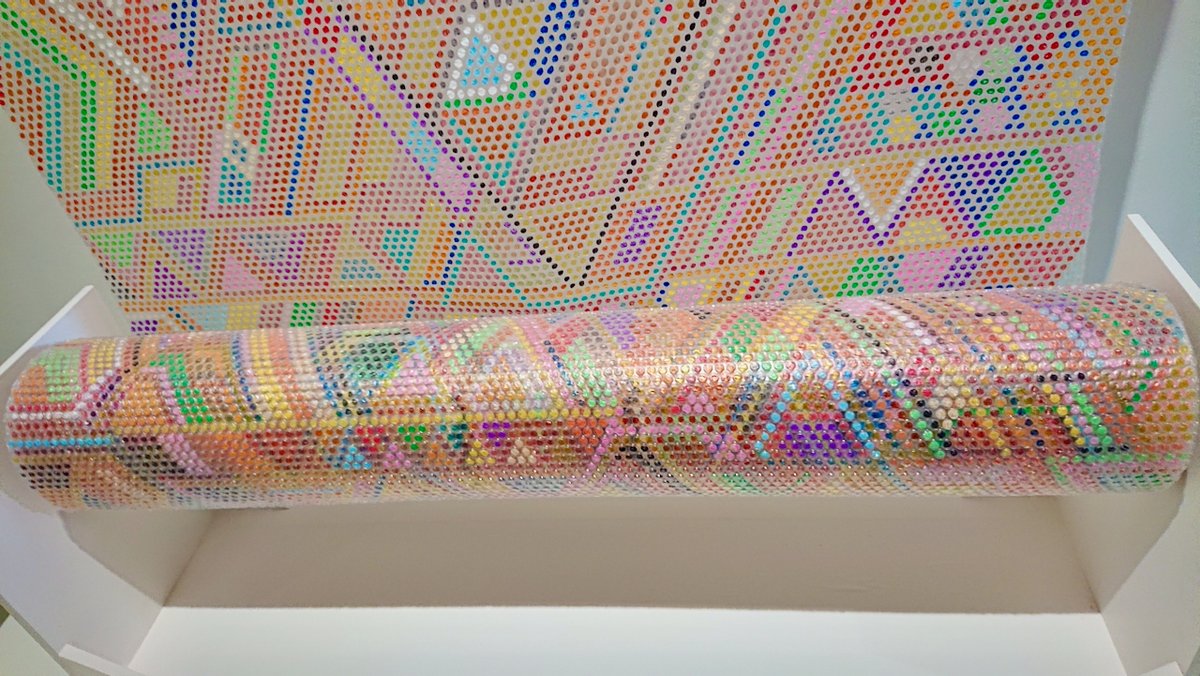

A waterfall.

“Hey. You’re kidding,” I realized that my words had become blurred with a sigh. There was a waterfall of dots. It was so powerful that I hesitated to even approach it. It reminded me of the awe I felt when I visited the waterfall. It was a completely different size from the work I was facing now. Its width was about the same as a 6-year-old child’s outstretched arms, about a little over 1m. Its length, or rather its height, was so high that I had to look up, so it must have been over 2m, or even more.

But that’s not all. The top of the waterfall and the basin were wrapped in thick rolls. In other words, the unfolded part was much longer. “Hey, how long do you think this is?”

“Hmm, I don’t know. About 100 meters?” “That’s too long.”

“So 10 meters.” “What do you mean?” Perhaps unable to bear to watch us as we played dumb games, or perhaps just because we were annoying, a staff member spoke to us. “It’s 20 meters long.” “Wha-aat?”Our voices echoed off the gallery walls in unison.”They say 20 meters.” “How long is 20 meters?” “About the length of your school swimming pool.” “Hmm.” You get the idea.

A waterfall. Or perhaps the program code of this world. I feel an endless flow of order, even chaos, built into it. It was the first time I felt speed from a still picture.

Perhaps when we die, our souls drift between dimensions like this, waiting for the next moment. “By the way, this one is 40 meters long,”

I said over the staff member’s head. There was something there that was completely beyond comparison. “A river. A wave, or maybe a dragon?” The scale was too large to fit in one’s line of sight. The balance with the exhibition space was strange to call it a work of art. If this was a work of art, then the ceiling and stairs must have been works too.

“I see.” A 43-year-old with a reaction not much different from that of a 6-year-old. I realized that when people are truly surprised, they become insensitive to the events in front of them. It easily exceeded my ability to be surprised. My brain’s hyperventilation and defense instinct. I’m sure I wasn’t this surprised when my father, who had disappeared, reappeared after 16 years.

I held my daughter’s hand tightly. And we looked up at the work that seemed to swallow us up. I wanted to be swallowed up. I wanted to go somewhere, swept away by the colors. For a while, I didn’t feel like moving.

I want to call it “full stomach painting”

We were already full. After the first piece, we were exhausted, but what awaited us were pictures of food menus.

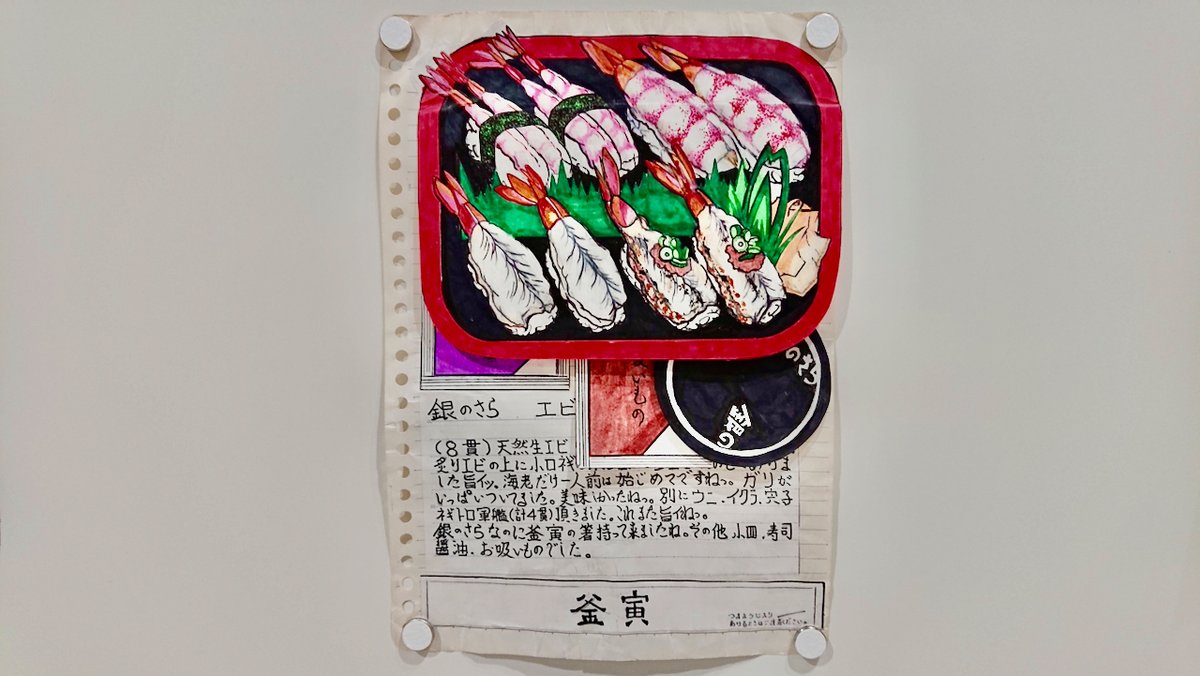

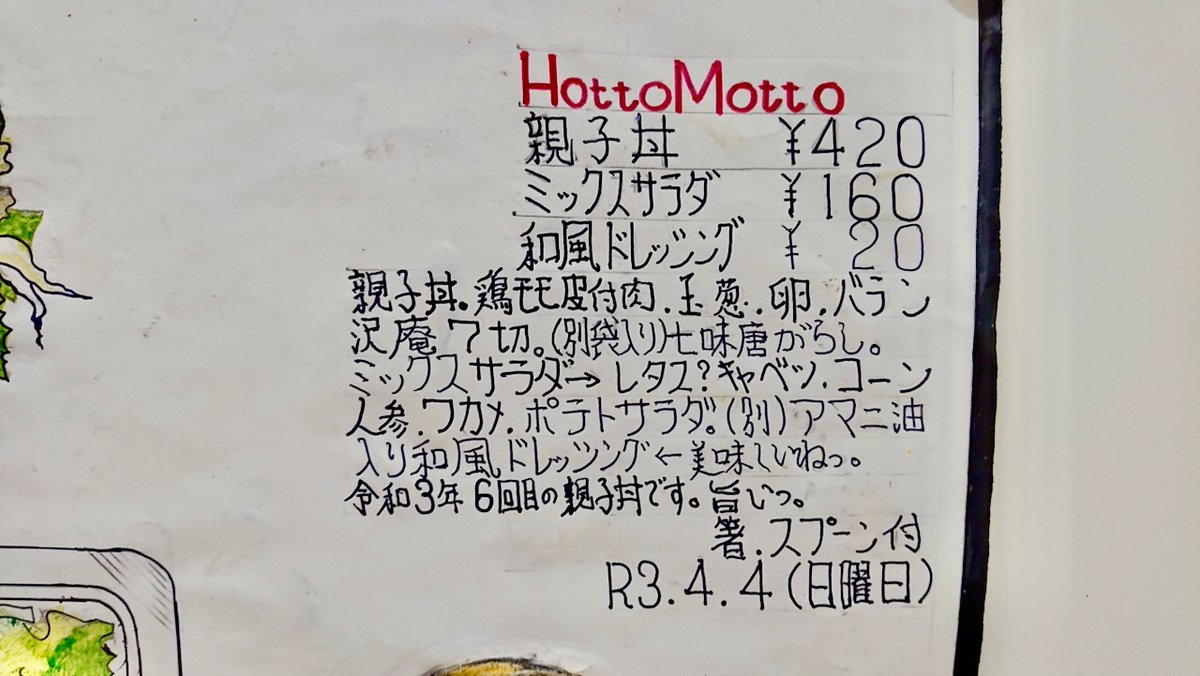

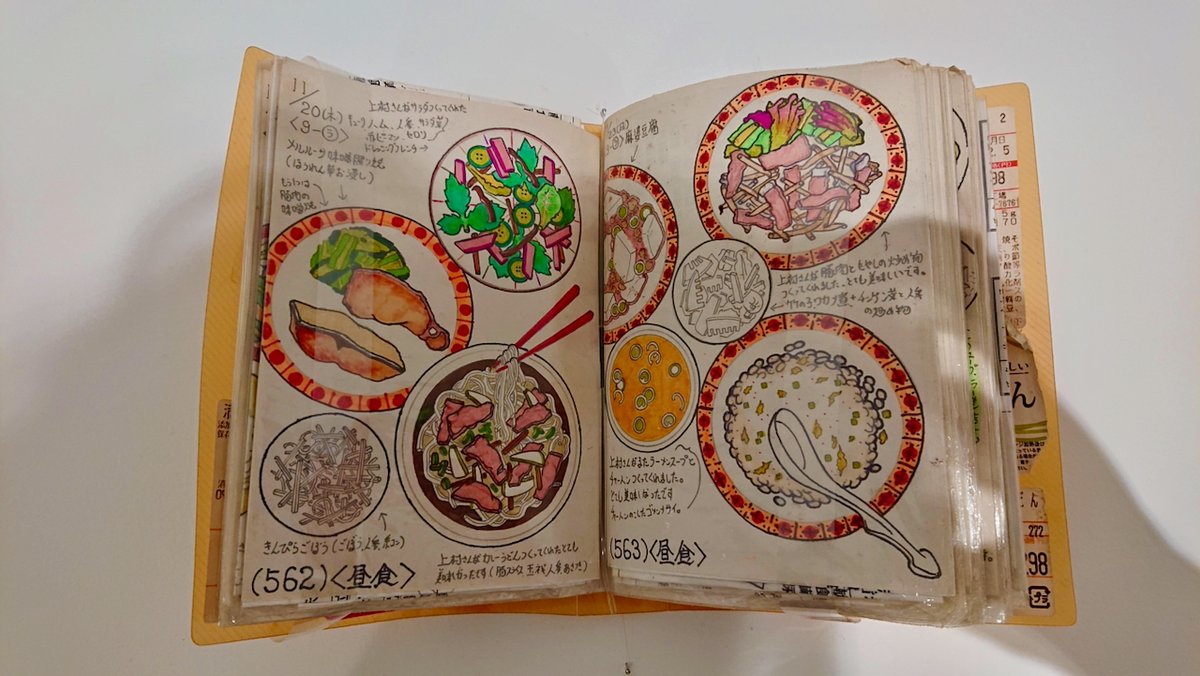

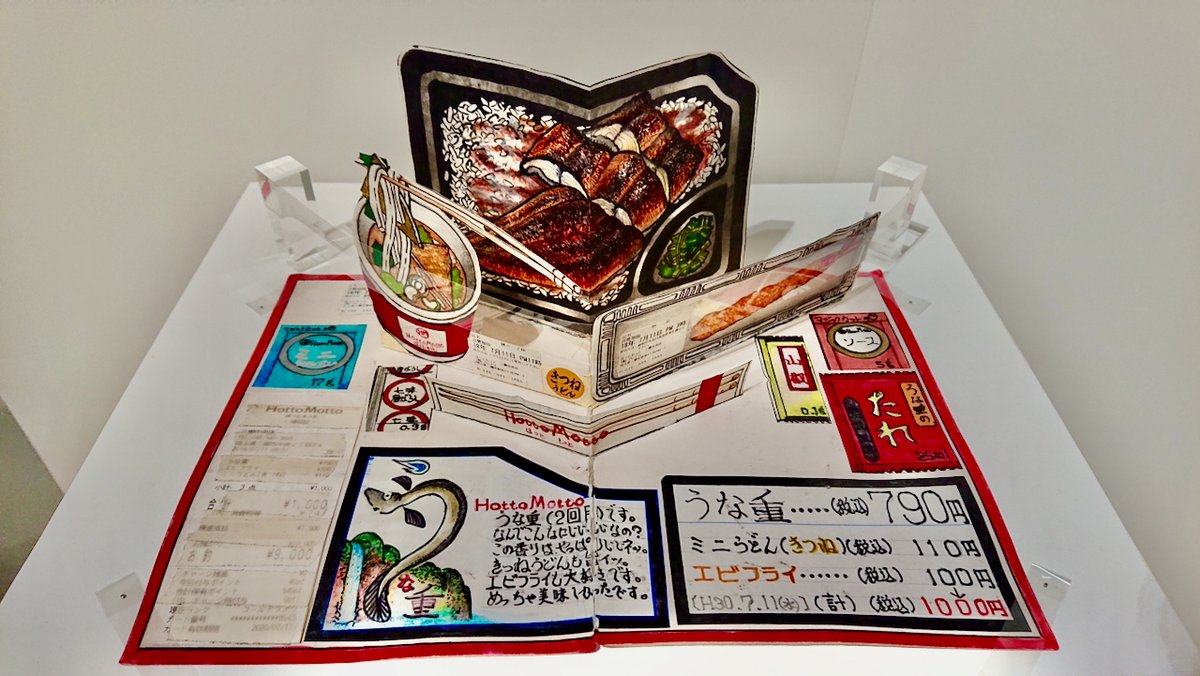

What is a picture of a food menu, you may ask. It is nothing but a picture of a food menu. Grilled mackerel bento. Makunouchi bento. Eel bento. Pork cutlet bowl. Oyakodon. Sushi bento. Fried rice. Kinpira burdock. Pork miso grill. Curry udon. Pictures of all of these. And they were shockingly detailed. “Is this a food sample?” They were not food samples. Just to be clear. Not only the main dish, but every single strand of noodles and every single grain of rice were carefully drawn. It seems they were trying to reproduce the taste, texture, and aroma. Even the way the food was arranged on one side of the plate or in the bowl was so realistic that I felt like I was seeing a carefree yet endearing depiction of everyday life.

As I stared at it, licking it, or rather eating it, something caught my attention. It was somehow strangely sexy. Or perhaps seductive. After hearing an explanation from a staff member, I understood why. And at the same time, my perspective on the work changed completely.

The work was not realistic. The artist was looking back at his accumulated notes, recalling memories of the day he ate it. In other words, he was painting a picture of “that day’s meal was delicious.”It was not a picture that looked appetizing. It was a picture of something delicious.

Bright memories were present in every corner, from the color and shape of the ingredients, the shine, the arrangement of the plate, and the angle of the chopsticks. Vividly. It’s likely that this sexiness could not be expressed by simply painting the food in front of you.

The euphoric feeling of a full stomach. You might even call it joy. You pat your stomach, saying, “Phew, I’ve eaten so much.” That moment was depicted in this work. There are paintings that make you hungry when you look at them. There are movies and music, too. But this was the first time I’d come across a painting that makes you feel full when you look at it.

“Look at this! Isn’t it amazing?” I said to my daughter, but her reaction was “Hmm.” Again. My daughter didn’t take the bait. Apparently it looked too real and normal.

Come to think of it, when I was in elementary school, we were always made to draw pictures after a field trip. The theme was “Memories of the field trip.” There was always someone in my class who would draw pictures of their lunchboxes. Even though my friends would tease me, saying I was greedy, or that’s why I was fat, somehow I would end up with a masterpiece. That was me. Maybe the artist was in that kind of mood when he drew it. If so, that time must be something to be savored, too.

“It was wonderful. Thanks to you I enjoyed it.”

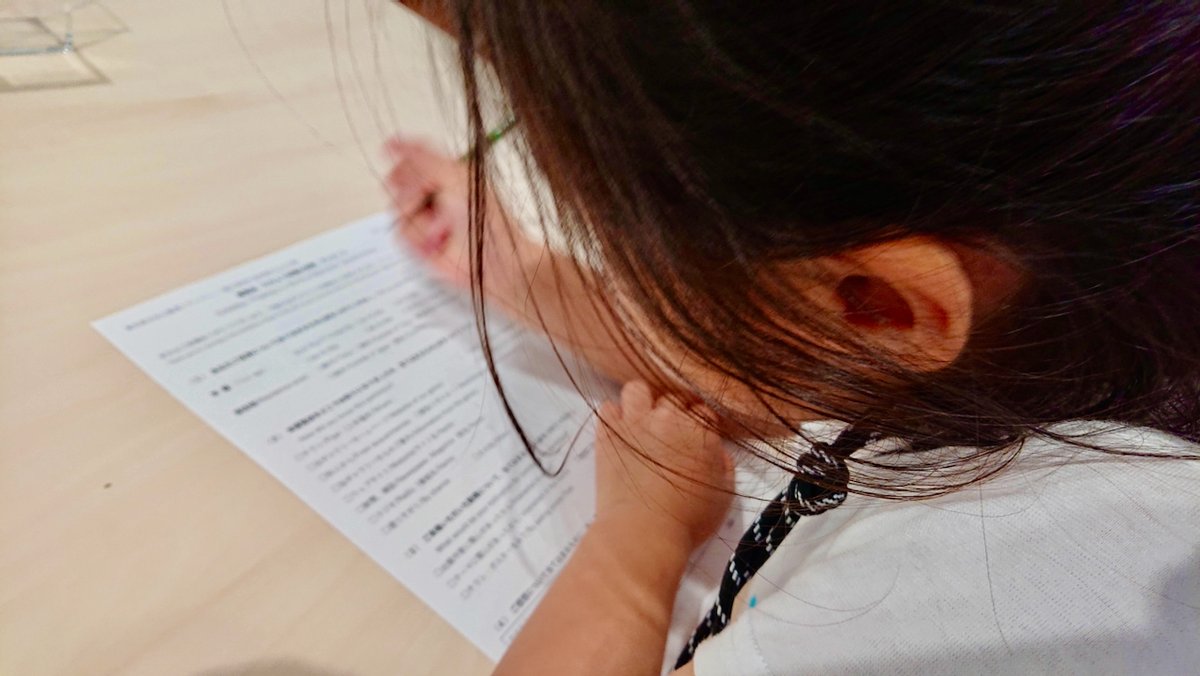

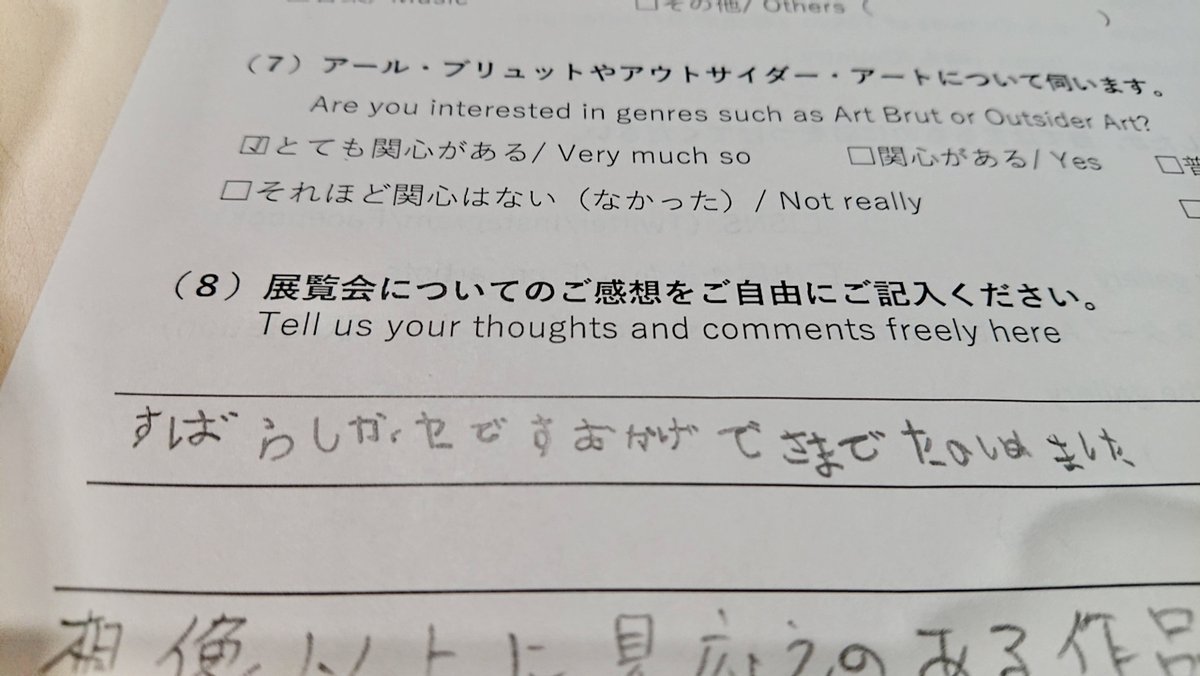

There were other works on display that were eye-catching, or rather, eye-catching, but a 6-year-old’s concentration doesn’t last that long. When her mouth was about to zip, we decided to leave and fill out the questionnaire. It

was my daughter’s first questionnaire ever. “Where do I check?” “Where do I write?” she asked me, occasionally holding her breath as she wrote. Her elementary school homework had already paid off. “It was wonderful , thanks to you, I enjoyed it.” Even though she was a child, she must have realized that the expression “

thanks to you” was disrespectful. She added “thanks to you.” It seems she hasn’t learned punctuation yet. The fact that she had something to write in the questionnaire meant that she found the exhibition fulfilling. As if casting a clean vote, my daughter respectfully placed the questionnaire in the mailbox.

On the way home, while eating Baskin-Robbins ice cream, I elaborated on the creators of the exhibition. “All the works we just saw were made by people with disabilities.” “Have you ever heard of disabilities?” “You know, some of your friends are O-kun and K-chan,” I started to say, but then stopped myself. I felt like I was drawing a huge line.

Or rather, my daughter wasn’t listening to what I was saying at all. She patted her slicked-back hair with a spoon and ate it lovingly. It’s an ice cream shop, so I wish the ice cream was creamier, sweeter, and more flavorful.

Aside from preferences in ice cream, everyone has their own way of looking at and feeling about art. There is one way to appreciate it, trusting only your own eyes without knowing the artist. There is another way to appreciate it, guided by interest after getting to know the artist. Both are fine. It’s also fine to say, “Disabilities don’t matter to art,” or “It’s amazing despite the disability,” or “It’s a style that could only be created by a disabled person.” But… Isn’t it boring to stop there? Is it

really true that disabilities don’t matter to art? Would I have come to this exhibition if the artist didn’t have a disability?

Amazing despite the disability? Amazing because of the disability? No. None of that mattered with the works I encountered that day. They had an overwhelming presence that didn’t require any preamble. I was excited intuitively.

For starters. Even though they are disabled. Because they are disabled. Can we fully appreciate the work from that perspective? There are certainly differences between us and them. To dismiss them as the same feels like belittling their disabilities. So then, what are the differences between us, and how is the quality different? Or rather, who is “us”? This question leads directly to the next question, such as “they,” or “humans,” and the difference between us and them becomes more elusive.

So what is disability art? It is a somewhat awkward category that tends to separate us from the other side.

We call it contemporary art, but we don’t call it contemporary art. We call it Western art, but we don’t call it Western art. However, disability art is often referred to as such. I think the real joy lies in questioning the danger of such categorization and encountering the breadth and depth of the world.

How does my daughter feel? As she sips from her long-empty cup and stares intently at my ice cream, I ask her the question. “How was your day?” “It was fun. I wish Mom had come too.”Mom. Not Mom, Mom. When my daughter is serious about something, she unconsciously and strategically uses “Mom.”It’s the best if the artwork makes you want to invite someone you like to come along. The viewing experience is wonderful. What more could you possibly need? With that one word, I felt like I was finally able to take a deep breath.

Until then, I had been suffering from stress due to interpersonal relationships at work, and suffered from insomnia and hyperventilation. I could manage the insomnia with medication, but the hyperventilation was a pain.

At night, I dreamed of drowning. I would wake up in pain. Thank goodness. It was a dream. Oh no. I still can’t breathe. The nightmare continued even after I woke up.

Soon, I started to have more and more breathless moments during the day, and the time spent in those moments became longer.

I had been suffocating under the closed, homogenous, and restrictive rules of companies and business partners, and I had completely forgotten that the world is wide, filled with all kinds of people, and living by rules I could never have imagined. And that there are wonderful encounters out there that make you want to invite your special someone. In other words, the world isn’t all that bad after all.

I thanked my daughter.

Me: “Thanks for hanging out with me today.”

D: “Thanks for hanging out with me.”

Me: “I was the one who got to hang out with you.”

D: “I want to come again.”

Me: “There were some shows I haven’t seen yet.”

I handed her my ice cream, which hadn’t yet melted. “You

haven’t forgotten about the arcade and Village Vanguard, have you?” my daughter asked, putting the heart-warming chocolate mint into her mouth.

<End>

Photos

コメントを残す